The cases below are common real patient cases. Names, images, and details have been changed for privacy purposes.

Psychiatric Crisis

“This is an emergency. Hang up, and call 911.”

A primary care telehealth practice has been seeing a patient for the past year. Late January she told her psychiatrist over telehealth she was going to kill herself. The psychiatrist said this was an emergency and told the patient to “hang up and call 911” to receive in-patient care. The provider hung up, and the patient did not call 911. A few days later she called her psychologist, said she was going to kill herself by taking pills, and again was told to “hang up and call 911.” The patient hung up and did not call.

A primary care telehealth practice has been seeing a patient for the past year. Late January she told her psychiatrist over telehealth she was going to kill herself. The psychiatrist said this was an emergency and told the patient to “hang up and call 911” to receive in-patient care. The provider hung up, and the patient did not call 911. A few days later she called her psychologist, said she was going to kill herself by taking pills, and again was told to “hang up and call 911.” The patient hung up and did not call.

On Tuesday afternoon the next week, she took a whole bottle of hydroxyzine pills and OTC pills. A few minutes later she called her telehealth practice in Little Falls, NJ and told them she had “done something stupid.” She was several hours from her home address. The clinic had emergency telehealth protocols and was able to activate 911 to her location. She became altered to the point she could not open the front door, so the provider coordinated with police and EMS to enter the residence and identify the pills taken. She made it to the emergency department and survived.

The patient’s psychologist and psychiatrist did not know the patient had not gone to the ER as instructed on their calls or that the patient had 911 activated for her suicide attempt until the telehealth provider’s office called them a few days later.

After Hours Phone Call

A 74-year-old male called his provider’s office because he was having epigastric and chest pains. The after-hours answering service transferred him to an available provider. The patient said he usually has pain when he eats spicy foods, but this time it was lasting longer and felt more like a squeeze. Antacids were not helping. He has a history of coronary artery disease. His niece insisted he call his doctor. The provider asked him to call 911 to which the patient agreed and hung up.

A 74-year-old male called his provider’s office because he was having epigastric and chest pains. The after-hours answering service transferred him to an available provider. The patient said he usually has pain when he eats spicy foods, but this time it was lasting longer and felt more like a squeeze. Antacids were not helping. He has a history of coronary artery disease. His niece insisted he call his doctor. The provider asked him to call 911 to which the patient agreed and hung up.

Thirty minutes later the provider called him back to see how things are going. His niece picked up and said he did not call 911 because he was afraid of getting COVID at the hospital and did not want to go. The provider again spoke with the patient and activated Telemedicine911. He arrived at the emergency department and was diagnosed with an inferior wall myocardial infarction.

Home Monitoring

A 55-year-old female was being evaluated for COVID-19 exposure and monitored on mobile cardiac telemetry (MCT). She was being managed by a nurse practitioner (NP) who was 130 miles away. The patient had a history of cardiac arrhythmia and poor compliance with beta blockers. The NP noticed an alert on the remote monitor and started a video conference with the patient. The patient was in full supraventricular tachycardia (SVT). She had no chest pain but felt light headed. The provider activated Telemedicine911 and contacted EMS. Paramedics arrived in minutes with PPE protection for COVID and initiated treatment on site. The patient was transported to the emergency department where her heart rate eventually normalized.

A 55-year-old female was being evaluated for COVID-19 exposure and monitored on mobile cardiac telemetry (MCT). She was being managed by a nurse practitioner (NP) who was 130 miles away. The patient had a history of cardiac arrhythmia and poor compliance with beta blockers. The NP noticed an alert on the remote monitor and started a video conference with the patient. The patient was in full supraventricular tachycardia (SVT). She had no chest pain but felt light headed. The provider activated Telemedicine911 and contacted EMS. Paramedics arrived in minutes with PPE protection for COVID and initiated treatment on site. The patient was transported to the emergency department where her heart rate eventually normalized.

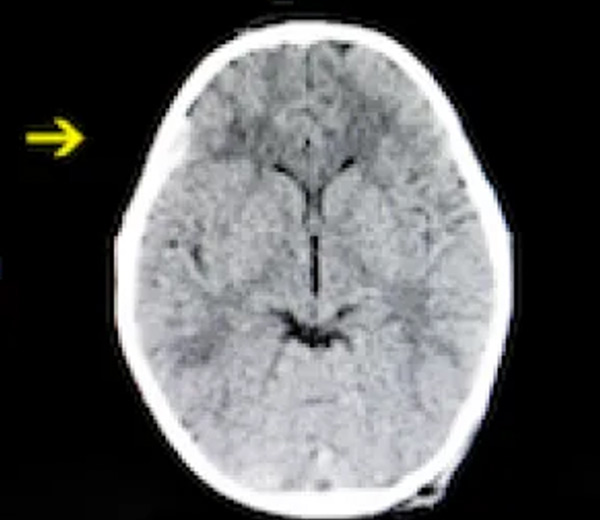

Radiology Callback

A 42-year-old patient was seen in the emergency department for a headache after a fall. The CT scan was normal as per tele-radiology. The patient left and went home to a different city. The next day on follow up the patient was found to have a subdural hematoma, which was missed on CT. When the doctor called, the patient’s headache had worsened, and he was somnolent. He coordinated the emergency response with Telemedicine911 to take the patient to their affiliated facility with neurosurgical operating rooms. The patient completed the procedure within the hospital system, had a short post op stay, and was discharged home to follow up.

A 42-year-old patient was seen in the emergency department for a headache after a fall. The CT scan was normal as per tele-radiology. The patient left and went home to a different city. The next day on follow up the patient was found to have a subdural hematoma, which was missed on CT. When the doctor called, the patient’s headache had worsened, and he was somnolent. He coordinated the emergency response with Telemedicine911 to take the patient to their affiliated facility with neurosurgical operating rooms. The patient completed the procedure within the hospital system, had a short post op stay, and was discharged home to follow up.